19 - Reflecting on the 9/11 attacks, twenty years on - Alex Urwin

“Remember when we faced unbearable pain with unbreakable strength.”

A handful of dates are etched into our collective memory, some joyous, others profoundly sad.

On September 11, 2001—a clear morning no different to the one I find in New York today—terrorists attacked monuments to capitalism, freedom and democracy across America’s East Coast. Hijacked planes—their hijackers intent on bringing death and terror to a watching world—felled the World Trade Center and brought smoke and bloodshed to Pennsylvania and the Pentagon. 2,977 people were murdered, 67 Brits among them.

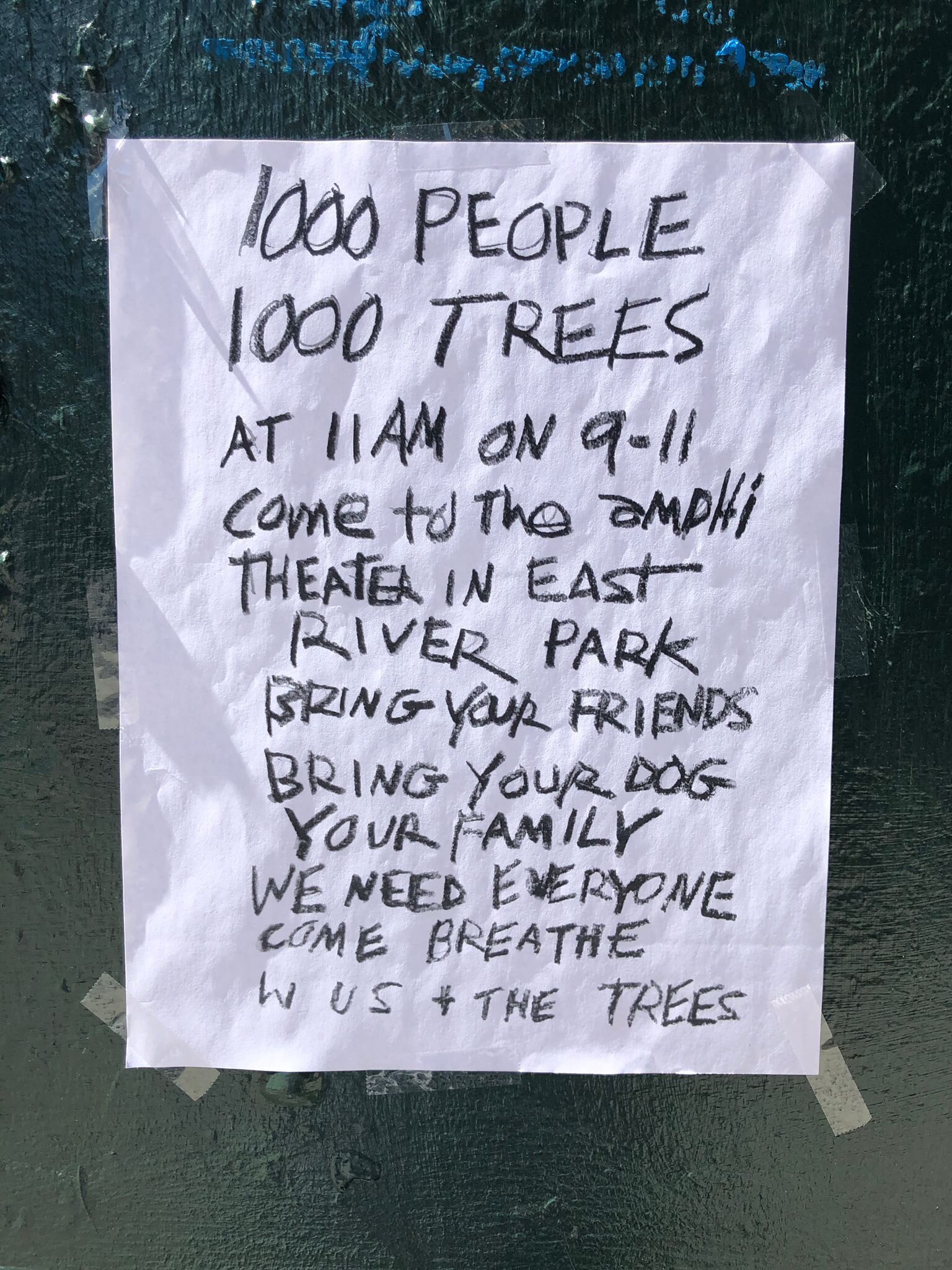

This September, the twentieth anniversary of the attacks, makes for a curious moment to arrive in the city. The posters lining the lounges at JFK invite travellers to head to Manhattan and celebrate the post-Covid awakening of the “greatest city in the world”. This celebratory mood is reflected in the atmosphere and programming from Broadway to Brooklyn. But looking a little closer, it is clear the city is reflecting and preparing to mourn; from hastily daubed graffiti to municipal billboards, New Yorkers are promising to “Never Forget”.

Plaque outside of the 9/11 Memorial & Museum, taken by Alex Urwin

In spending a morning walking the streets around Ground Zero, this reflectiveness is at its most apparent. There is a separate discussion to be had on our approach to memorial; there was something jarring in the tourists posing for photos at the fountain, while the group arriving at the museum in a stretch limousine showed no apparent reticence in their rendition of happy birthday. But there is a deeper sense of unease in our ongoing acts of remembrance, with the discomfort surely rooted in the increasingly complicated legacy of the attacks.

A former tutor described his experience of being in New York on the day of the attacks and in the weeks that followed, recalling “the acrid dust that seemed to sink upon the city every evening, as temperatures fell and anxieties rose”. In a moment of sentimentality, he reflected on a feeling of becoming a New Yorker, bonded to the city and its residents in sorrow and then extraordinary resolve. It was that feeling of resolve—a resolve embodied by President Bush as he called on his country to “go forward and defend freedom”—that moved the American government and national security establishment in the immediate aftermath. The Bush doctrine was established and its central point, that America would make no distinction between terrorists and those harbouring them, marked the beginning of the war on terror. Congress passed the Homeland Security Act and the intensely controversial PATRIOT Act. In months, the ability of the state to invade the privacy of its citizens expanded hugely, while judicial oversight and public accountability were seriously undermined.

Ground Zero Memorial, taken by Alex Urwin.

So, with this reaction in mind and the perspective of twenty years, it would appear the attacks successfully shook the foundations of America and the liberal, open societies that comprised the American-led international order. As shock gave way to anger, so began a period of pervasive fearfulness that guided foreign policymaking across the West. In the US specifically, the expanded power of the president and the security apparatus, ballasted by a willing Western coalition, led to the incredibly costly invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq. Indefinite periods of detention at Guantanamo Bay soon followed. Additionally, we saw the securitisation of domestic life, and nations and their communities increasingly driven apart; President Bush had to remind his country that Muslims were not pariahs to be feared or attacked. Twenty years on, in the chaos of the eventual withdrawal from Afghanistan, America and its allies are facing existential questions relating to these two decades and, by extension, their role in the world.

There has been much that is good and remarkable too. The exceptional memorial museum dwells poignantly on those who ran towards the chaos in order to save others, rather than running away. In walking the streets around Ground Zero, one shares space with people from every nation, faith, and creed, each proof that America remains open and for so many as a place of great hope and opportunity. There is also something truly powerful in the decision to erect a new tower where the Twin Towers fell, a feat of engineering that stands as a monument to America’s defiance. There is something brilliantly American in the Westfield, the beer gardens, and the gift shops that stand on the site too.

The New World Trade Center in NYC.

But while these acts of hope and peaceful resolve are stirring, there is clearly a need to refocus. The harrowing scenes from the evacuation of Kabul airport should be testament enough to that. Domestically, inter-community strains and suspicion of ‘Other’, rooted in the fear and anger that followed the attacks, are as potent as ever. One needs only to consider the immediate surfacing of debates about the extent to which the West can house Afghan refugees. The threat of attack persists too, both from established and disruptive state and non-state actors. As the Taliban resumes control of the country it was driven from twenty years ago, the need to better understand and engage the agents of those threats is patently apparent. As Biden leads America and its allies in eschewing military intervention, working out how to engage these actors via deterrence, whether diplomatic or otherwise, is clearly the next defining challenge.

If the US are to rise to this challenge, a reset is surely required. Biden must not press irreversibly along the path to isolationism laid for him by Obama and Trump. America remains too important—militarily, economically, and politically—and indeed too responsible for the ongoing instability in the Middle East to abandon its role as an international leader. There is a role for the UK too, and a similar decision as to our role in the world. The UK government’s Integrated Review is certainly interesting, not least in its commitment to consolidate world-class cyber capabilities to effectively navigate one of today’s most vital planes of conflict. But the Review’s seeming dependence on the US, at the expense of due regard for vital allies across the EU, is problematic. Further, where a ‘Global Britain’ ambition promised much, in the absence of a compassionate approach to the ongoing refugee crisis or overseas aid spending, many would argue that the UK is presently falling short.

Those at the forefront of this challenge would do well to reflect on the names etched onto the fountains that stand where the World Trade Center once stood. In those names and all those who survived them, there are countless reminders of our extraordinary capacity for service and sacrifice. Indeed, the anniversary memorial fund invites us to “remember when we faced unbearable pain with unbreakable strength”. It was this idea that Obama was channeling five years ago, on the fifteenth anniversary of the attacks, as he said that “in the end, the most enduring memorial to those we lost is ensuring…that we stay true to what’s best in us”. These sentiments should surely guide Biden and the US—standing alongside the UK and other allies—to ensure that, far from abandoning their global role, they are looking outwards and seeking a bold and compassionate foreign policy agenda, whether in memorial or in response to the threats and challenges that remain.